United Screens for Palestine is an open and decentralized collective of programmers, cultural workers and venues, responding to the paralysis brought about by the ongoing genocide as well as the increasing policing, censorship and criminalisation of everything Palestinian. As a collective, they aim to make each screening a space for conversation, learning and most of all, mobilization. As they state:

At Le Guess Who? 2024, United Screens for Palestine presents a program with films and discursive moments. Below the collective, together with Le Guess Who? artist Asher Gamedze, provides context around their program and introduces the films that will be screened during the festival.

Words by Asher Gamedze, Reem Shilleh and Omar Jabary Salamanca

This piece’s title comes from “War Within a Breath,” a Rage Against The Machine song from their 1999 album, The Battle of Los Angeles. The song draws connections between the struggles of the racialized urban poor against the predatory landlords of the Southern California metropolis, the Zapatistas’ fight against NAFTA (North American Free Trade Agreement) and the Mexican government’s attempts to dispossess the country’s peasantry, and the Palestinians’ Intifada against Israeli occupation. Lyricist Zack de la Rocha does this elsewhere too, on “Township Rebellion,” from their self-titled debut, he insists that “Freedom must be fundamental in Johannesburg, or South Central [Los Angeles].” What he highlights through the internationalist connections that he draws, is the centrality of land in urban and rural areas to human life, the projects of colonialism, capitalism and imperialism – and of course, struggles against them.

As humans cannot live permanently in water and have not developed the capacities to live in the air or in space, terra firma is essential to life itself. It is the basis of all forms of productive human activity, agriculture, manufacturing, etc., even fishing requires land in the form of harbours or ports. We need it for dwelling, for recreation, and for all forms of social, spiritual and cultural life. There are multiple ways that different groups of people relate to land – some understand themselves to be a part of it and establish relations with it accordingly, others see it as a means of accumulating profit and, many, or most who live under capitalism, are forced to rent the land they live on from the state or landlords. How different groups of people relate to each other in society is often mediated by land and the conditions of its ownership – workers uprising against mine owners over conditions of work deep underground, landlords extorting tenants, community sport events at a local field, or people performing spiritual ceremonies at the beach. Land is autonomy, allowing people to determine the shape of their own lives.

One of the most striking is the year 1948 which meant different but related things. In South Africa this year is generally marked as the beginning of apartheid – when the white electorate voted in the Nationalist Party. It also marks the Nakba, the great catastrophe of mass Palestinian dispossession and the establishment of the state of Israel. What is important about these two histories and the emphasis on 1948 as a major moment, is that while the year was undoubtedly significant, it was by no means the beginning.

From the battle of Salt River in 1510 when the Khoi battled and defeated the mischievous Portuguese; the Dutch-Khoi wars of the mid-late 1600s; the hundred years of war waged mainly against amaXhosa from 1779-1878 (which expanded the British colonial frontier east from the Cape); to the Land Act of 1913, which legally consolidated Africans’ dispossession and allocated 87% of the land for whites, the voracious Dutch and British settlers had long lusted after the pastures, rivers, and underground minerals of Southern Africa.

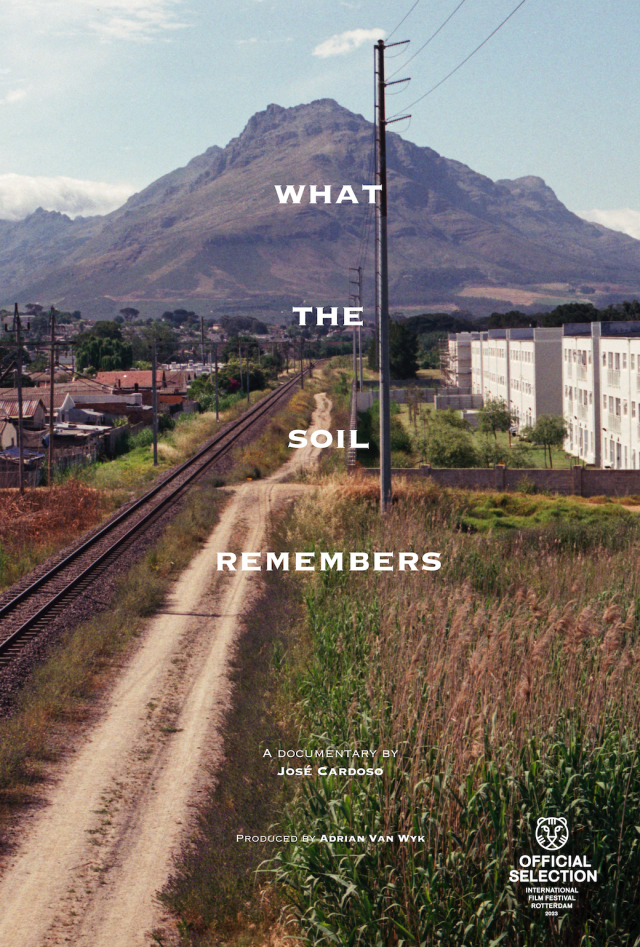

By the time the apartheid government entered the scene, they merely picked up the baton, upped the ante and continued in the tradition of those who came before them. This is important background to What the Soil Remembers (2023) which explores the memory of forced removal of a black community in Stellenbosch to make way for a white university. One of the paradigmatic forms of apartheid dispossession strategies – dispossessing black people of their land and citizenship in South Africa – was the Bantustan. As Last Grave at Dimbaza (1973) shows, the Bantustan system was the economic and social basis of apartheid: a system of oppression and exploitation that was built on top of the already-existing dispossession and disenfranchisement of the indigenous population.

Mainstream discourses that supposedly explain the escalating violence of the Israeli state in the wake of 7 October 2023 tend to obscure the nature of the antagonism. The red herring of destroying Hamas, for example, operates as an alibi for the Zionists’ designs. Ben Gurion, first prime minister of Israel, anticipating the state’s establishment was far more honest about the project, he said: “After the formation of a large army in the wake of the establishment of the state, we will abolish partition and expand to the whole of Palestine.”[1]

Like some of the images of expanse and seeming desolation in Scenes From the Occupation in Gaza (1973) show, it should be clear that the Zionist vision for Gaza is to make sure that land is all that is left. They want to make true their historical falsification that Palestine is a land without a people – this is the central preoccupation of Zionist statecraft – to facilitate its occupation. This preoccupation was expressed most explicitly in the very process of the Israeli state’s establishment which was organised, modern mass-scale genocidal violence:

The 1984 film Ma'loul Celebrates Its Destruction gives some glimpse into these horrors at a village-level. While this period around 1948 was the major moment of mass Palestinian dispossession, it had been envisioned for half a century by the political Zionist movement. It been planned and prepared for, with increasing intensity, since the beginning of the mandate period in 1922: The successive waves of settlers, the establishment of the “proto-state” Yishuv and the Zionist paramilitaries and terror-groups like Haganah, the IDF’s predecessor, collectively made the Israeli offensive possible.

While 1948 acts as a pivot point in both the Palestinian and South African struggles, 1993/1994 is also a key shared moment - the Oslo Accords and the beginning of the so-called post-apartheid period, respectively. The dynamics and limitations of the transition in South Africa restricted the possibilities of any radical mass-scale land reform. And for Palestine, Oslo reconstituted and shrank the Palestinian geography (from the river to the sea) into fragmented and fragile bantustans where land dispossession could continue. In both these places, like many others in the world, the land question remains central to the maintenance of the status quo, ongoing struggles and the pursuit of autonomy.

Landed Reel-ations, put together by United Screens for Palestine, creates space for conversing about the multifaceted dynamics of the land question within the historical and contemporary struggles in Palestine and South Africa.

[1] https://decolonizepalestine.com/intro/the-mandate-years-and-the-nakba/

[2] https://www.aljazeera.com/features/2017/5/23/the-nakba-did-not-start-or-end-in-1948