On November 9, 2019, the Greek polyphonic vocal ensemble Isokratisses gave a rare performance at the Jacobikerk during Le Guess Who? Festival in Utrecht, The Netherlands. Founded by Anna Katsi, the group dedicates itself to the polyphonic singing of Poliçan, an ethnic Greek village in southern Albania. All the members are women who developed their musical experiences together since their childhood; the project represents the desire to maintain a locality in the way of singing, as something that comes to life again through their voices.

Now, Le Guess Who? releases the full recording of the performance, as well as a listening and reading session by author, producer, archivist and musicologist Christopher C. King that preceded the concert.

Text by Jasper Willems.

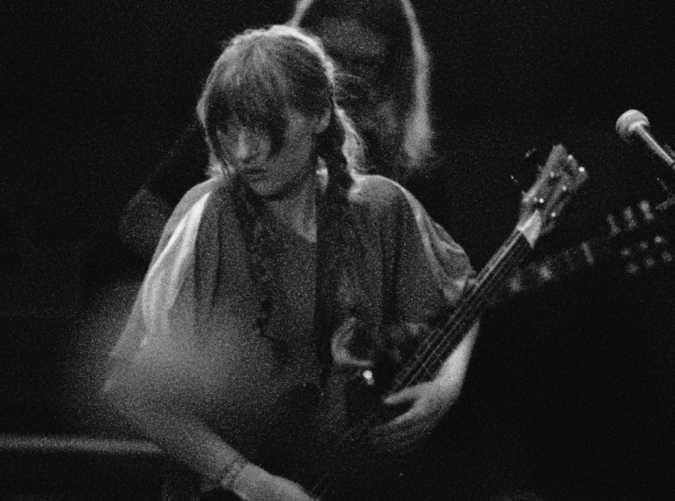

Photography by Melanie Marsman (part of the Hidden Musics Photo Series).

Live recordings by Marc Broer.

by Melanie Marsman.jpg)

As our senses gradually become dulled by standardised notions of sound and performance, Utrecht’s Le Guess Who? festival challenges audiences to experience music in unfamiliar ways. Pushing the most cutting-edge artists to the forefront is, of course, one way to achieve this. But sometimes it’s actually the most ancient of music that allows a person to feel something completely new.

This often entails music that derives from extreme remote, isolated parts of the world, free from industry-based institutions. One example is seven-piece vocal ensemble Isokratisses. This group performs polyphonic folk songs from Epirus, a mountain region stretched across Northern Greece and the Albanian mainland. Because of Epirus’s singular geographical attributes – including the vast mountain ranges of Albania, a land already pretty remote from Western influence – this music has remained an exclusive force of celebration and hardship for centuries, passed down generation by generation. Isokratisses are the latest wielders of this singular musical heritage. Not just its elemental power remained unchanged since the Byzantine age, its culture and customs have stayed intact as well, which means this is the oldest active form of folk music in Europe.

It was a profoundly beautiful experience hearing these lamentations, known as miroloi, fill the reverb-inducing acoustics of the church. It must have been a bit unusual for the performers themselves as well: they were not used to singing these songs within the hierarchy of a stage performance with an attentive audience. After all, this is music for remembrance and reflection, performed at informal social gatherings, parties and wakes within the stirrings of daily life in Epirus. Melodies sung to rejoice in the passing of existence.

A miroloi is generally speaking pentatonic in structure, which means that each vocal or instrumental piece consists of five notes (though there are deviations). During the performance, each of the women took turns as the central narrator, while the other six responded in unbroken harmonic splendour. These vocalised lamentations and their distinctive arrangements form a “fundamental need to mourn and heal”, according to author, producer, archivist and musicologist Christopher C. King.

Before Isokratisses took the stage, King led a listening and reading session providing some rousing and colourful context concerning the history and inner workings of Epirotic folk. Reading a passage from his book Lament from Epirus: An Odyssey into Europe's Oldest Surviving Folk Music, he described how the “curative, healing function” of the miroloi transformed him profoundly, discovering this singular folk movement after stockpiling on 78 rpm discs.

“For those who don’t know what an old 78 is”, King continued, “it’s basically an old recording like an LP, but more fragile, and to me, estimably more valuable because it captures time. It’s as if you’re sticking history with shellac. Because of me growing up in America and collecting these discs, it dawned on me that what I loved was dead. It had developed beautifully when it was recorded, but it no longer existed. I thought that all vibrant folk music had died.”

by Melanie Marsman.jpg)

Isokratisses live at Le Guess Who? 2019, captured by Melanie Marsman.

Full Hidden Musics photo series here.

Except it hasn’t. After realising the practice of miroloi was still very much in perpetuity in North-Western Greece, King became enraptured with everything Epirus-related: the region’s pagan roots, cultural landscapes and social customs. He was keen to point out the music’s “selfless” purpose as opposed to contemporary music, pulling no punches in his assertions. “In modern music I hear self-centeredness, a constant referencing of individual artistic expression. It is all about ‘me’. But in the old music I love, I hear selflessness, continuity and communal expression. It was all about the ‘we’.”

King delineated the surprising similarities between old American blues and Greek blues, playing a recording from 1928 by Mississippi John Hurt’s ‘Candy Man Blues’ and a recording made by Giorgos Katsaros from 1929. Both recordings capture music as a raw and urgent extension of the performing individual. It resets a fundamental question about the original purpose of why people make music in the first place.

Though some may disagree with King’s assessments, it’s hard to deny the impact of music that’s somehow remained unspoiled by commodification or mass marketing. Since our brains are overtly conditioned to hear Westernised pop structures with choruses and verses, this music awakened something very foreign and primal from within. As the unearthly voices of Isokratisses bellowed out, it felt as if new synapses started firing across unmapped areas of the soul; a wave of unprocessed emotions came pouring out like from a faucet.

As King cogently reminded those who were present: “Music as a balm for the unknowable and inevitable.”

The performances of Isokratisses and Christopher C. King were part of the first instalment of Le Guess Who?’s Hidden Musics program, in collaboration with producer Ian Brennan and Glitterbeat label founder Chris Eckman. Ustad Saami, Pakistan’s last living khayál master, was another performer at the Jacobikerk during the festival’s 2019 edition, introducing a dying discipline to new ears. Now and in the future, Hidden Musics aims to present global music traditions – rich and often centuries old – that normally don’t reach our shores. Music from more remote parts of the world preserved in amber as it were, as vital and potent today as during their conception.

You can exclusively listen to the full live recordings of Isokratisses and Christopher C. King above, captured on November 9, 2019 at the Jacobikerk Utrecht.

by Melanie Marsman.jpg) Isokratisses & Christopher C. King backstage at Le Guess Who? 2019, captured by Melanie Marsman.

Isokratisses & Christopher C. King backstage at Le Guess Who? 2019, captured by Melanie Marsman.

Full Hidden Musics photo series here.