Based between Amsterdam and Berlin, Insan Larasati is a community organizer, DJ, designer and inclusivity officer. With artist Shasti Andara they founded Nusaqueer Diaspora, an open-structured collective that focuses on community events for the Indonesian and Southeast Asian Archipelagan queer diaspora.

Freshly graduated from the Willem de Kooning Academy (Rotterdam), Insans research-driven and collaborative practice is based around community organizing and queer diasporic identities. Their work is influenced by their life as a queer person of color, their history as a child of immigrants and political activists, and their experience working in EDI (Equity, Diversity and Inclusivity) at the WDKA Office for Inclusivity.

In 2024, U? collaborates with five different NL-based community curators who will highlight their communities and creativity. Insan Larasati and Nusaqueer Diaspora organize an event that explores how Indonesian and Southeast Asian Archipelagan queerness lives on, is reinterpreted and reinvented through its diaspora, at Tigers Gym on Friday, 8 November.

The following article is an edit of Insan’s BA thesis (June 2024) and is written from their perspective.

Photography by Shaunak Mahbubani, Shastika Andara, Savannah van Berkel.

This paper follows my experiences during the name finding journey of Indo*queer Diaspora, drawing from conversations with community members as well as my own research into histories and theories behind terminology, naming and queer diasporic identity. It looks at the names I’ve used for the community: Indoqueer Diaspora, Nusaqueer Diaspora and Indo*queer Diaspora and analyses how their meanings and histories frame the community in different ways. By doing so I touch on the broader question of identity and commonality within the Indonesian queer diaspora in the Netherlands, analysing what it means to be a diverse, intersectional community and how queerness and displacement affects our identities.

A diverse community

In 2022, me and Shasti Andara organised our first event for the Indonesian queer diaspora as a reaction to the lack of queer Indonesian representation during Documenta15. We both see ourselves as part of the Indonesian diaspora, while having differences in our identities and heritages, mainly that I grew up in the Netherlands with Sundanese parents, and Shasti, with Batak, Jawa and Sundanese ancestry, grew up in Jakarta until they moved to Kassel ten years ago. Differences in heritage and history are apparent for those who belong to the Indonesian diaspora. An example of the many different histories of the Indonesian diaspora in the Netherlands: People who are ‘Indisch’ and descend from the Indonesian immigrants who came after Soekarno banished those who worked for Dutch companies in 1957 (Andere Tijden, 2023). Descendants of several hundreds to a thousand political exiles who fled after the 1965 ‘communist’ genocide (Hill, 2022). Javanese-Surinamese people descended from the Indigenous people of the Southeast Asian Archipelago (now known as Indonesia) enslaved by the Dutch in the period of 1890-1930 to work on plantations in Suriname. And the many Indonesian students who come to the Netherlands to study, and sometimes stay here to work. These histories are inherently linked to the colonisation of Indonesia and also an indication of class and privilege: enslaved people who worked on plantations in Suriname came from working class backgrounds, while people who were ‘Indisch’ lived more privileged lives due to their close connection to the coloniser to uphold the Dutch East Indies.

The Indonesian queer diaspora also consists of different generations of immigrants: those who were born in Indonesia and came here to study or work (1st gen), those whose parents moved abroad and were born outside of Indonesia (2nd gen), and those whose Indonesian ancestry dates back to their grandparents or great grandparents (3rd and 4th gen). Some community members feel greatly connected with their roots, supported by being able to speak the language or growing up with families practising Indonesian traditions, while others grew up being less close with their roots, with only the knowledge of having Indonesian ancestry, and strive to reconnect with the culture they weren’t taught at home.

Indoqueer

Me and Shasti decided to call the event we organised for Documenta15 (2022), ‘Indoqueer Diaspora Clubnight’. While the process of naming began out of the practical necessity of finding a name for the events we organise, things started to get more complex when me, Shasti and other members of the community started to identify with the name and call ourselves Indoqueers.

We soon ran into bigger questions: What represents the Indonesian queer diaspora? What brings us together? On what commonalities can we build our community?

Shasti came up with the name Indoqueer Diaspora Night for our event, which resonated with both of us. By fusing ‘Indo’ and ‘queer’, they did not have to be two separate, perhaps even contradicting identities. The need for separating Indonesian and queer identity is something I see a lot of people in the Indonesian diaspora struggle with. It’s a frequent topic in conversations with my community and a lot of Indonesian queer diasporic artists’ work don’t often speak about being Indonesian and queer as components of one identity. I noticed this for example in Prins de Vos work, one of the speakers of the event ‘Indo* & Queer: een postkoloniale erfenis’, held in November 2023. His explicitly queer photography work contrasts his video project ‘A Collection Of Broken Ideas’, a video that references his Indonesian heritage, where queerness is much less present.

Indoqueerness and patriarchal nationalist ideologies

Why can’t queerness and being Indonesian exist in the same space? State imposed cis- and heteronormativism, like the 2022 law outlawing sex and cohabitation outside marriage, making queer sexualities illegal since marriage is only allowed for cishet couples (Bisset, 2022), makes being queer in modern-day Indonesia potentially difficult and dangerous. It gives the entirety of Indonesia the reputation of being anti-queer without distinguishing Indonesia as an institution and government, and Indonesia as a people, who should not be generalised.

The queerphobia of the Indonesian government is tied to its modern state structures and relatively new ideologies. During the reign of the New Order, President Suharto institutionalised the family principle (azas kekeluargaan), closely associated with the Javanese ideas of Ibuism; a social construction of womanhood based on a societally determined idea of domestication and productivity (Hyunanda et al., 2021, p.1.), and Bapakism, where the ‘bapak’ is the ‘leader’ of a family, an informal institution, or as an attitude, which demands obedience in particular from those of lower status – defined by being younger in age, junior in work status, or culturally ascribed as having lower status in formal relationships (Irawanto, 2019). After the fall of the military dictatorship of President Suharto in 1998, discourse of human rights and women's rights emerged (Wieringa 2015b) and gay and lesbian people attempted to stake a claim in the public sphere and tried to set up or strengthen various sexual rights groups (Boellstorff 2005; Wieringa 2007). The violence against queers, especially gay men, that followed was rooted in the belief that non-cishet identities threatened the gendered ideologies of the ‘ideal citizen’ (Boellstorff, 2004), and in doing so the status-quo. This erases the fact that non-heteronormative and non-cisnormative identities, practices and kinships are abundantly present in traditional practices in Indonesia (Talogo, n.d.; Boellstorff, 2004, p. 470) and existed peacefully for many centuries. An example is the five gender-system in the Bugis tribe in Sulawesi; makkunrai and oroani, corresponding to concepts of cis men and women, calalai who are born with female bodies and take on more ‘traditionally’ male gender roles, calabai are born with male bodies but take on ‘traditionally’ female gender roles and bissu, spiritual beings who embody the totality of the gender spectrum and act as intermediaries between worlds and occupy a shaman-like role in Bugis religion.

The name ‘Indoqueer’ serves as a reminder that ‘queerness’ or non heteronormativity / non cisnormativity is deeply ingrained in Indonesia. It looks beyond the state induced patriarchal values and its internalisation, instead it affirms the queerness that has always existed in Indonesia.

The Indoqueer in diaspora

‘Diaspora’ is the third facet of the intersectional identity of Indoqueer Diaspora. In an Instagram post appearing accompanying the announcement of our first event, Shasti wrote: “[The Diaspora is inherently queer] To be in diaspora and never fitting in just one label in this white patriarchal world-construct. ‘Indo’ as a white-man’s word that floats around in ‘Indonesia’, ‘India’, ‘Indo-China’, etc. etc. But also ‘indo’ as colloquial word we in the Indonesian archipelago use to call ourselves, to shorten ‘Indonesia’ because its fucking 4 syllables long (no wonder, a white man’s invention!)” (Shastika, 2022). Being in diaspora, whether as someone who grew up in a culture different from one's parents (Editors of Merriam-Webster, 2023) or as an Indonesian immigrant, inherently means being part of an identity that is outside nationalist narratives. Both me, who grew up in the Netherlands with Indonesian parents, as Shasti, who grew up in Indonesia but has lived in Germany for 10 years, feel like we don’t fit within the labels ‘Dutch’, ‘Indonesian’ or ‘German’.

It is important to consider what or who is considered ‘Indonesian’. State adoption of the ‘ideal citizen’ as cis- and heteronormative transferred to the displaced Indonesian and became a symbol of strong cultural ties to the nation of origin. A parallel can be made to Gayatri Gopinath (2005, pp. 18-20) in her text ‘Impossible Desires’ where she talks about how gendered constructions of South Asian nationalism are reproduced in the diaspora and how this results in rendering the queer diasporic subject as ‘impossible’. The cis- and heteronormative ‘‘woman’’ is used as the boundary marker of ethnic/racial community in the nation the diasporic community settles; embodying the past homeland and cultural ties to it, fulfilling the role of modest girl, wife, or mother, upholding the values of patriarchal nationalism disguised as ‘traditional Indian values’. This puts the non heterosexual Indian woman in a space of impossibility; she is excluded from the roles and symbols that women are expected to inhabit and represent within the diaspora: the “lesbian” can only exist outside the household, community, and nation of origin, whereas the ‘‘woman’’ can only exist within it. The ‘lesbian’ is seen as ‘foreign’, a product of being in the West too long, and therefore part of the West and not Indian, rendering the queer Indian woman as impossible.

The same thing goes for the ‘Indoqueer’; to be Indonesian and queer is rendered an ‘impossibility’ by the Indonesian state and means being erased from the space of household, community and nation of origin. A lot of Indoqueers further explore, develop or even discover their queerness in diaspora, leading to the assumption that queerness is inherently Western. The Indoqueer is therefore not seen as Indonesian; a lot of Indoqueers feel like they have to ‘shed’ their queerness when entering the space of household, community and upon returning to Indonesia, in order to be accepted as ‘Indonesian’.

‘Indoqueer’ resituates questions of home- as domestic space, community space, and national space, by asserting the ‘Indoqueer’ in dominant national and diasporic narratives, rejecting the idea that we pose a threat to family, community, or nation and refusing to categorise the Indoqueer as alien.

‘Indo’ and white supremacism

In September 2023, a year after Indoqueer Diaspora Clubnight, I collaborated with friends for another Indoqueer Diaspora event, this time in Rotterdam. Shasti, being based in Germany and increasingly busy, took a step back from co-organising. During and after the event, which was called 'Toko Poing by Indoqueer Diaspora' and held in the arcade/club Poing, I received feedback that some people were doubtful about coming to the party because of the use of ‘Indo’. One of the reasons was the misunderstanding that the party was intended for those of mixed Indonesian and European origins, since in a Dutch context, ‘Indo’ is often understood as someone with mixed Indonesian and European blood.

After the party I did research into the history of ‘Indo’. In the Dutch East Indies, being ‘Indo’ allowed for the privileges such as the right to a Dutch citizenship. ‘Indo’s’ and fully Indigenous people with close trade relationships to the Dutch gained access to learning the Dutch language, which in turn gained you access to jobs for Dutch companies or the Dutch state (Van Selm (n.d.)). Considered closer to the coloniser, they formed a new class who called themselves ‘Indisch’ and helped sustain the colonial rule of the Southeast Asian Archipelago (later known as Indonesia).

Proximity to whiteness plays a big role in being ‘considered Dutch’. In White innocence: Paradoxes of colonialism and race, Gloria Wekker says about this: “Belonging to the Dutch nation demands that those features that the collective imaginary considers non-Dutch—such as language, an exotic appearance, een kleurtje hebben, “having a tinge of color” (the diminutive way in which being of color is popularly indicated), outlandish dress and convictions, non-Christian religions, the memory of oppression—are shed as fast as possible and that one tries to assimilate” (Wekker, 2016, p.7). In Indonesia, the wish for proximity to whiteness lives on in internalised white supremacist beauty standards, with having white features; fair skin, tall physique, straight hair, double eyelids, being deemed beautiful, intelligent and successful. Unsurprising, many Indonesian celebrities are of mixed Indonesian and white descent (Simanjuntak, 2014).

It is not at all what Indoqueer Diaspora stands for, as critical reflection on the colonial past and especially its consequences for us as a community plays a big part in the conversations we have. The question I posed in my essay ‘Het I-woord’ also rings true here: Can we really decolonize if we still use our coloniser's tongue and in extension, our coloniser’s mind? And if we value decolonising our own minds wouldn’t another name be more appropriate?

‘Indo’ and local identifications

‘Indo’ refers to Indonesia, but during the Toko Poing party, I discovered that not all members of the community identify with being Indonesian. The Moluccan diaspora in the Netherlands for example, were descendants from ex-KNIL soldiers who were promised independence by the Dutch after the fall of the Dutch East Indies. In 1950 the quickly suppressed separatist movement known as the Republik Maluku Selatan (RMS) lead to many thousands being forced to relocate to the Netherlands where they, after being used as a weapon against the nationalist movement in the former Dutch East Indies, were forced for many years to live on the fringes of society, dreaming of an eventual return to their homeland which they had hoped one day to liberate (Witton, 2007).

The distaste for being called ‘Indo’ is also shared by West-Papuan community members, whose independence movement is struck down violently by the Indonesian government with over 500,000 West Papuan civilians having been killed and thousands more having been raped, tortured or forcibly disappeared (Free West Papua Campaign, 2021).

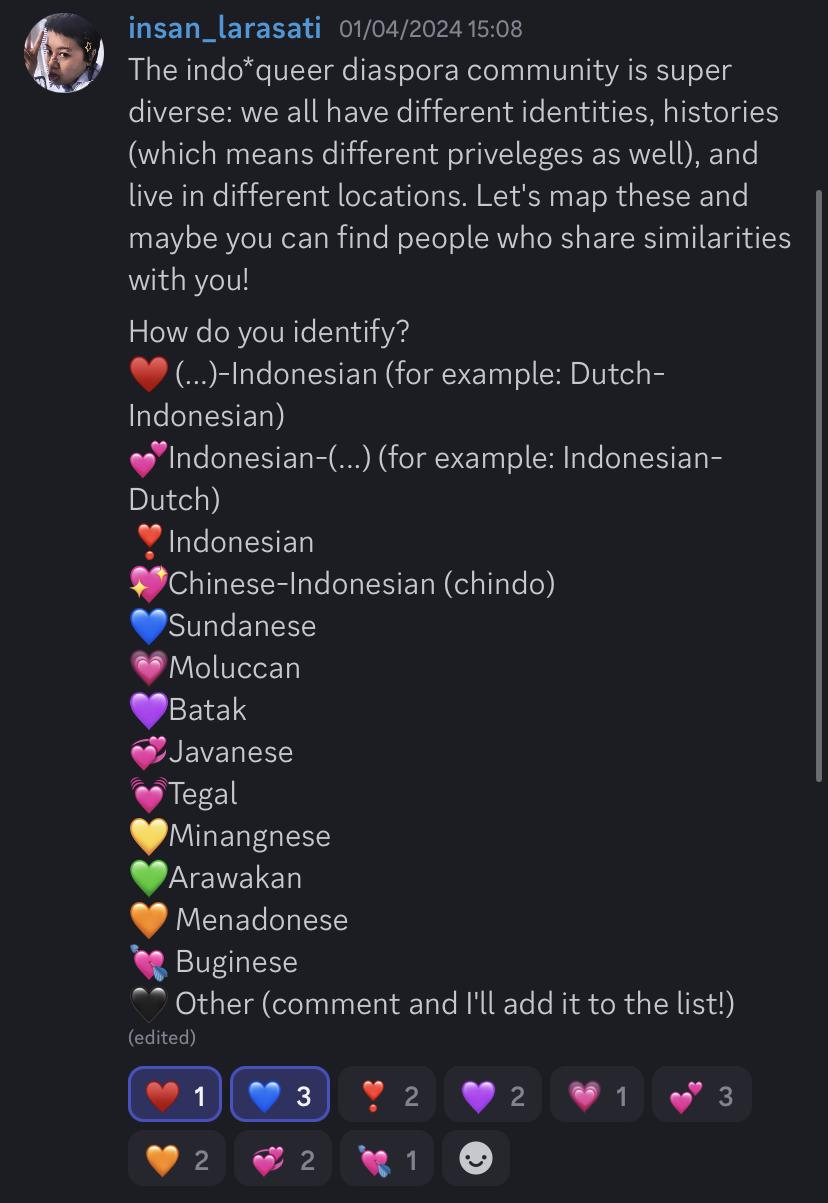

Instead, they introduce themselves based on their ethnic or local identities; Menadonese, Javanese-Surinamese, Jaksel (from Jakarta Selatan), or Chindo (Chinese-Indonesian), and usually a combination of two or three. This was most notable when I started creating community channels for the Indonesian queer diaspora on Whatsapp and Discord in March 2024 and the introductions came flushing in; a member of our community introduced themselves as Jakarta-born Batak/Jawa/Sunda based in Germany, for example. Ethnic groups in Indonesia have their own culture, language, script and cuisine and are centuries old, as opposed to the relatively new identity of ‘Indonesian’. Nationalism puts emphasis on a shared identity, with ethnic nationalists even politicising its culture by redefining, re-educating and regenerating the ethnie and its members. By doing so, they ‘purifying’ the community of ‘alien’ elements, which in turn may lead to the expulsion and even the extermination of minorities, the 'outsider’ within (Smith, 1994). In Indonesia we see ethnonationalism in the politicising of Javanese culture by adopting Javanese family values or Islamitic values (the most prominent religion in Java) in politics, or in the genocide of ‘65 on Chinese-Indonesians and the ‘66 law on compulsory name change to more ‘Indonesian’ sounding names (Yao Kan, 2018). I doubted whether ‘Indo’ did the intersectional identities of our community justice and continued practices of ethnonationalism.

‘Nusa’ and various criticism

In November 2023, I started collaborating with Poing again. This time to organise a Lunar New Year party in February 2024, in collaboration with Scattered Waves, a radio show showcasing diasporic southeast asian electronic music (mainly from the Vietnamese community and diaspora), and Eastern Margins, a record label and platform for alternative Asian culture. Having to make an Instagram page for Indoqueer Diaspora for promotion, I had to make a decision on the name. After sharing my doubts about the name ‘Indoqueer Diaspora’ on Instagram, some people from the community suggested I adopt the name ‘Nusantara’, which they explained as a pre-colonial name of Indonesia and another word for archipelago, which has a history of being used as an alternative name for Indonesia such as by writers and novelists during the anti colonial struggle (Evers, 2016). Thinking it bypassed the problems with the word ‘Indo’ I changed the name Indoqueer Diaspora to Nusaqueer Diaspora, writing a statement referring to the white supremacist origins of ‘Indo’ and how using Nusa acknowledges the Javanese imperialism that undermines independence movements in the RMS and West-Papua, showing support for these movements.

Criticism from members in the community followed, pointing out a contradictory statement since the Javanese ‘Nusantara’ meaning ‘outer islands’ was used by Gadjah Mada, chief minister of the Majapahit Empire that conquered an area stretching from modern day Malaysia to West-Papoea and therefore a product of Javanese imperialism.

Support for the independence movements in West-Papua and Maluku was also questioned, which was seen as a remnant of Dutch colonialism; during the anticolonial struggle, the Dutch promised independence to Maluku and West-Papua to undermine the Indonesian anticolonial movement. Questioned was whether the use of pre colonial terms like ‘Nusantara’ erases the struggle of those colonised and their independence battle. Indonesia is a country born out of colonisation, Indonesian nationalism was a tool to free the country from colonial rule, and displacement happens closely connected with the country's colonial history. As Gopinath says: "Just like discourses of sexuality are inextricable from prior and continuing histories of colonialism, nationalism, racism, and migration" (Gopinath, 2005, p.3), the same counts for discourses on diaspora. The diaspora cannot be separated from colonialism: why use a pre colonial (but still imperialist) name for a queer diasporic collective, when being in diaspora is inherently linked to colonialism?

In another conversation, a friend said that how a term was used historically doesn’t have to exclude us from using it now, taking the example of the word ‘Kanak’, originally a German swear word for Turkish immigrants, and now a name carried "with proud defiance" by the children and grandchildren of the first-generation migrants, becoming a synonym for a new and different "German-ness" (Özbek, 2017). The idea of giving names a new meaning made me think about whether we could give a new meaning to ‘Indo’.

The biggest advantages of using ‘Indoqueer Diaspora’ is that its target group is immediately recognisable, queers in diaspora who have roots in Indonesia, with the reference to Indonesia as a bordered area also having a disadvantage in its exclusivity. In casual conversation, both in Indonesia as outside by its diaspora, ‘Indo’ is commonly used as an abbreviation of Indonesia: “When was the last time you were back in Indo”, “I’m craving Indo tonight (referring to Indonesian food)”, “We’re starting late, Indo-style”. This exists alongside the fact that most people from Indonesia or the Indonesian diaspora identify more with their ethnic, regional or local identity. Would it be possible to use ‘Indo’ as a purely practical term while recognizing and highlighting the fact that not all members of the community identify with being ‘Indonesian’ and distancing ourselves from the meaning of ‘Indo’ as half European? Perhaps adding an asterisk or a plus to the word Indo could refer to these sidenotes? (Indo*queer Diaspora or Indo+queer Diaspora).

Indo*queer Diaspora as a tactical name and flexible identity

Perhaps if we see the name Indo*queer Diaspora as a tactical name, it's okay if it can’t fully represent us. Michel de Certeau makes a distinction between strategy as the overarching framework of the dominant institutions and their objectives and tactic as individual actions included in everyday activities and how ordinary people use and appropriate the products created by the dominant institutions (De Certeau, 1984, and Zaykova, 2014). Seeing the Indonesian queer diasporic identity and the name Indo*queer Diaspora as a tactical identity, uncovers how our existence and our gathering disrupts absolutist nationalist narratives, and even the institution of Western queerness, of LGBTQIA+. The West sees LGBTQIA+ or queer as the most progressive and ‘correct’ way to name people who belong to non heteronormative and non cisnormative identities, but by generalising all non heteronormative and non cisnormative as belonging to these names erases, and misses the intricate differences in local identities such as the calalai, calabai and bissu people in the Bugis tribe.

Trying to capture the queer Indonesian diasporic identity in one name, trying to find the ‘The Name For All Of Us’, makes the Indonesian queer diasporic identity fixed, unmoveable, exclusive and in a way an authority in itself; it’s like saying “You are Indonesian (erasing local identities and the intricacies of bicultural identities) and you are queer (erasing other terms describing non cishet identities), and in diaspora therefore you are Indoqueer Diaspora.” The task I unconsciously gave myself puts me in a position of authority, and who am I to decide what an entire community should be called?

The search for a name for the community thus became the search for an ‘essence’; a stable and unchangeable core of the Indonesian queer diasporic identity. In ‘Queer Diasporas’ Cindy Patton and Benigno Sánchez-Eppler (2000, pp. 7-8) talk about the dangers of over-emphasizing this core identity in the face of displacement, criticising traditional theories that state that identity is either transportable or entirely socially located. Instead, they say that when displacement happens, whether that be between spaces that are officially designated (like nation, region, metropole) or more abstract (like culture, gender, religion, disease), complex realignments of identity, politics, and desire occur that are caused by the interaction of personal identity and the social and political contexts. When we cling to a ‘core’ when displacement happens, we tend to frantically search the apparently parallel structures of their race, ethnicity, nationality, gender, and sexuality to resecure what they suddenly feel like mismatched and struggling essences.

In the process of searching for a name, I experienced constant mental displacement. With every new knowledge I gained or conversation I had, I felt like I was constantly moving between cultures, ideas, contexts and histories, frantically trying to realign the name and my understanding of Indonesian queer diasporic identity. But identity formation is such a complex and individual process that it cannot be generalised nor captured in one name. Besides, as Sanchez-Eppler and Paton said “...if frantic realignment is all we do, we risk ignoring the full effect of moving on the elemental swirl of identity. We risk underutilizing the power of tactical maneuvers, of queer timings, to alter territory, to leave burn marks as our trace, to get a face from defacement“ (2000, pp. 8). By focusing my energy on trying to find the ‘perfect’ name, I assert fixed identities or essentialist narratives to the experience of displacement and risk ignoring the power that we have when we gather, connect with each other, and claim our space.

Indo*queer Diaspora

For now, I use Indo*queer diaspora, adding the asterisks and always explaining the many side notes it has.

I now understand the power of names and the importance of knowing the history of terms and the different meanings they hold to different people, influencing how the community is framed and who is included and excluded. The experience of displacement, as well as the shaping of identities, is a complex and constantly occurring experience making the Indo*queer diaspora a diverse, multi-facetted, intersectional, and fluid community that isn’t capturable in one identity or one name.

This doesn’t mean we shouldn’t gather. Last March, when I voiced my struggle on finding a fitting name to Shasti, they said to me: “It’s just a name. The most important thing is what we do”. I realised now that, fuck they were so right. My own experience and feedback from the community during events confirm that bringing together people from the Indonesian and Southeast Asian queer diaspora, no matter how their identification or history, is a joyful and affirming experience. Being able to create spaces where the Indonesian* queer community can experience joy and affirmation is the core reason for why I organise.

By gathering we actively subvert the nationalist image of the Indonesian* in diaspora. We reject that the ‘true’ Indonesian in diaspora is cis- and heteronormative, fulfilling roles adhered to nationalist patriarchal structures. We claim our place in dominant national and diasporic narratives by asserting our presence, refusing to categorise ‘Indo*queerness’ as alien. We subvert ethnonationalism by acknowledging, addressing and celebrating the diversity in ethnic, regional and local identities in our community and open up our gatherings to those whose origins lie outside the nation of Indonesia. We subvert the patriarchal idea of family, of azas keluargaan, forming kinship not based on sharing the same blood or gendered structures and roles, but on shared experiences, and choose ourselves what kind of roles we want to fulfil. This makes our gathering and queer joy resistance.

Note: reflecting back in October 2024

My thoughts and opinions are constantly evolving with every conversation I have. When describing my community at the moment I notice myself using ‘Indonesian and Southeast Asian (Archipelagan)’ the most. I’m looking forward to the conversations we’ll have at U?, where my program will feature a community dinner with open discussion with members of different Indonesian and Southeast Asian Archipelagan communities, about the topic of commonality, gathering and naming.

In 2024, U? collaborates with five different NL-based community curators who will highlight their communities and creativity. Insan Larasati will organize an event at Tigers Gym on Friday, 8 November.