COSMOS: Behind the Scenes with Liquid Architecture

In 'Behind the Scenes', COSMOS dives into local stories from across the world together with our global partners.

For over two decades, Liquid Architecture has grown from a student project to Australia’s premier festival for experimental and avant-garde music. In its current form, as a year-round program of innovative sound and music happenings, it continues to push boundaries and challenge norms. Berlin-based writer Caroline Whiteley spoke with Kristi Monfries, the artistic director of Liquid Architecture, to discuss the organisation's new creative direction and ongoing dedication to supporting Indigenous and Asian-diasporic artists.

Words by Caroline Whiteley

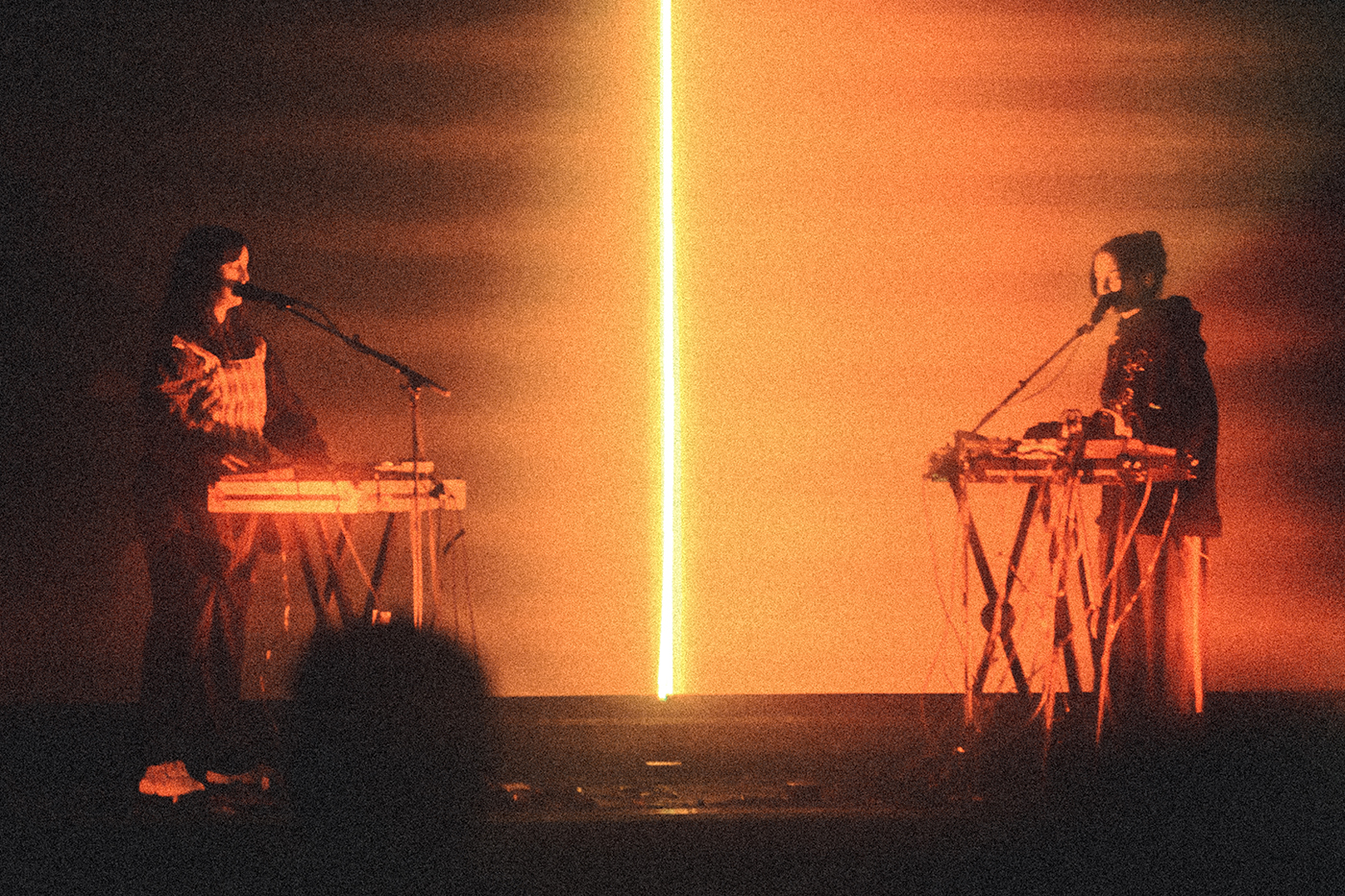

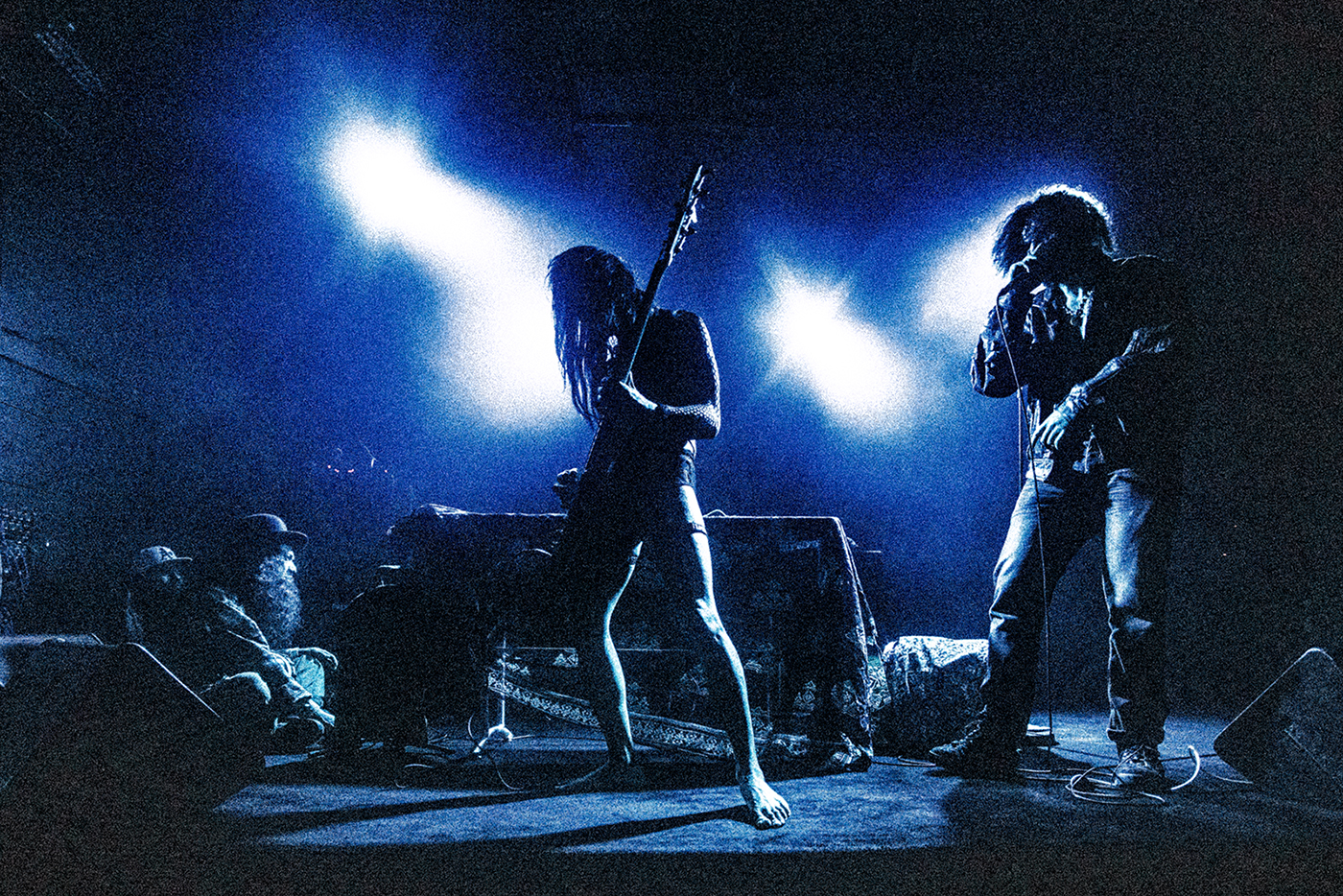

Photography by Young Ha Kim

Kristi Monfries is dialing in from her hometown of Yogyakarta, Indonesia. The Melbourne-based curator and director of Liquid Architecture (LA), Australia’s longest-running organisation showcasing experimental sound art practices, is here to connect local art institutions to build stronger cultural bridges between Australia and the Global South. “There has been a strong trajectory of experimental practice and sound practice here that [previously] wasn’t really given the attention that it deserves,” she comments.

Founded at the onset of the new millennium by students and faculty from the Royal Melbourne Institute of Technology School of Art (RMIT), the term is inspired by Venezuelan architect and musician Marcus Novak, who coined “Liquid Architecture” in 1991 to describe an adaptable and dynamic style of architecture existing in virtual space.

In the mid-2000’s, under the directorship of co-founder Nat Bates, Liquid Architecture expanded from a small local event in Melbourne to an annual touring festival and roaming showcase of experimental and avant-garde music and sound art. Until recently, LA was co-directed by Kristi Monfries and Lucreccia Quintanilla, with previous Liquid Architecture festivals hosting artists like Tony Conrad, Robin Fox, Oren Ambarchi & Martin Ng, Lawrence English & Ai Yamamoto, and Pauline Oliveros, who visited Australia for the first time in 2007 to perform at Liquid Architecture’s annual festival.

Monfries fondly remembers her time engaging with Liquid Architecture’s early shows. In 2003, during the fourth edition of Liquid Architecture’s festival, French composer Bernard Parmegiani led a “multispeaker diffusion” performance at RMIT’s Storey Hall, filling the space with his flawlessly recorded compositions, manipulating soundscapes using mixers and a variety of precisely positioned speakers. The audience was surrounded by a symphony of ticking and crunching, flipping and scribbling, cracking in and out of their consciousness. “I walked in as one type of person and came out another type of person. It was mind-blowing,” Monfries says. Throughout the years, “Liquid Architecture offered visitors many opportunities to engage with some of the great composers of the avant-garde Western canon.” During this time, experimental music moved from a fringe, “niche-y nerdy thing to be into” into an art form that is increasingly resonating with broader audiences and recognized by the Australian government’s funding structures.

However, Monfries believes that in the past, the Western experimental musical canon was often “celebrated to the detriment of many other practices.” As an organization that works with “sound” and “listening,” Monfries now wants to explore and interrogate more deeply what those words mean in different geographical contexts. When Monfries and Quintanilla first took the helm as Liquid Architecture’s co-director in 2022 following long-time director Joel Stern’s departure, they set their sights on showcasing more diverse artistic practices, with a specific focus on Indigenous peoples and the Asian diaspora.

Monfries explains that Australia’s demographics have changed significantly over the past couple of decades. There has been an increase in migration to Australia from Asian countries, including India, China, the Philippines, and Singapore, contributing to Australia’s cultural landscape in new ways.

One way Liquid Architecture works with different diasporic cultures is by offering creative cooks opportunities to share their food at its artistic showcases. At a recent concert showcasing Filipina-Australian artist CORIN, attendees had the opportunity to indulge in Thai noodle salad and Ghormeh Sabzi prepared by Ronen Jafari, also known as “My Name Chef”. Local chefs Dora Mazzeo and Matisse Laida, founder of Eatin Good (WEG), a platform for queer First Nations, Black, and POC to showcase food and identity will be offering food at the upcoming LA event.

Back in Yogyakarta, Monfries remembers food always playing an essential role at cultural happenings. “It’s almost like if you don’t have food at an event, there’s something wrong with you,” she jokes. “Everybody gets excited when there’s excellent food. When you’re feeding somebody and living in a cost of living crisis, that actually alleviates some of the financial burden [for artists].”

Like many countries worldwide, Australia is experiencing a cost-of-living crisis threatening the local artistic community. In March, the mental health organization SuicidePrevention Australia released data showing that people in Victoria have experienced the largest surge in financial strain compared to any other state in the country.

Despite the constant challenges the artistic community in Melbourne has faced in recent years, there have also been some victories. Over the next five years, Creative Australia has committed to increasing public funding for the arts, and after the lockdown, Liquid Architecture was able to move into a permanent home at Collingwood Yards, a state-funded creative arts precinct located near the Yarra River.

With its shiny exterior, designed by a prestigious London architecture firm, and its suburban setting, Monfries wasn’t on board right from the jump. “Constructed communities always seemed quite weird to me. You can’t just show up and make a community. It relies on conversations and relationships. Unless you’ve been through the hard yards with groups of people, then how do you really feel connected?”

Throughout their time at Collingwood Yards, however, Liquid Architecture fostered a strong network of collaborators and co-conspirators. Aside from the regular shows at their homebase in Collingwood Yards, Liquid Architecture hosts its events in various locations across the city, working in close partnership with other venues. “We have really strong relationships with the other organizations [based in Collingwood Yards]. It’s incredibly useful and advantageous to share resources.” A recent performance by sound practitioners Kusum Normoyle, Jannah Quill and Joee Mejias was held at The Mission to Seafarers Victoria, a heritage-listed building in Melbourne.

Looking ahead, Liquid Architecture will also continue collaborating with other organizations across Australia to offer international artists opportunities to expand their time in the country. San Francisco-based artist Victoria Shen aka Evicshen, recently did a workshop at LA whilst on tour, organised by Lawrence English the Brisbane-based artist and curator who often collaborates with LA. Living in a country that is vulnerable to climate disasters has only amplified the organisation’s efforts to facilitate longer exchanges with artists. “We just have to work together. Otherwise, it’s like, why would you burn all that carbon to get here for one show?”

Through their extensive digital sound and visual archive, as well as their online journal Disclaimer, launched in 2019, Liquid Architecture offers listeners a chance to engage with its activities online. "Being able to have long-form articles about particular artist practices is important," Monfries confirms. "It also acts as an archive of what's happened, and it gives a bit of a long-term insight into the thinking around why people were doing things at that time." Disclaimer features profiles, such as in-depth pieces on artists like Nina Buchanan and Kusum Normoyle, or discussions on the Palestinian struggle by Jamal Nabulsi and Han Reardon-Smith.

Liquid Architecture also emphasises moving forward the conversation around Australian Indigenous sovereignty. As a matter of respect, the organisation acknowledges its presence within the Australian context as a colonial-settler nation-state, recognising the Wurundjeri Woi Wurrung as the traditional owners and rightful guardians of the land on which they operate.

Are you interested in collaborating with COSMOS to share your local cultural scene? Please let us know via cosmos@leguesswho.com.